Over 39 million people will die from antibiotic-resistant infections between now and 2050, according to a comprehensive global analysis of antimicrobial resistance.

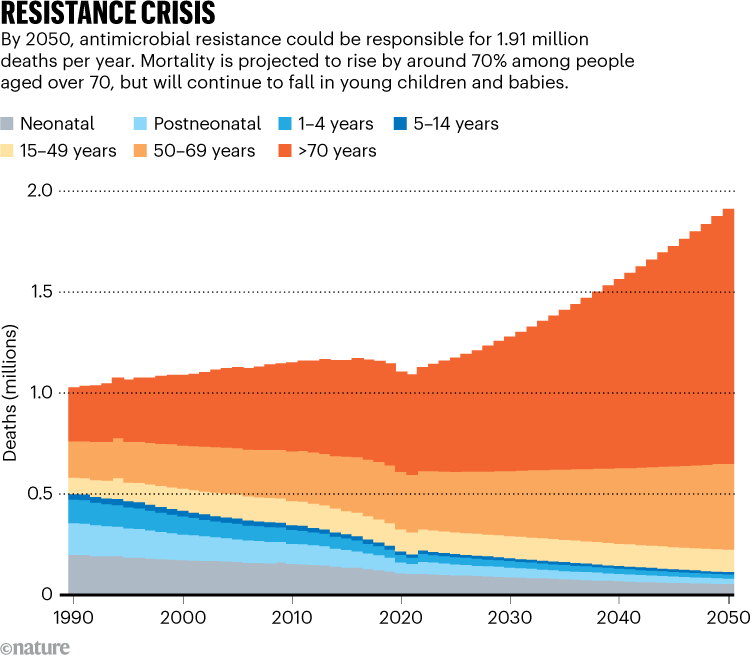

The report, published September 16 inThe Lancet 1, found that between 1990 and 2021, more than a million people died annually from drug-resistant infections, and by 2050 that number could rise to nearly 2 million. Around 92 million lives could be saved between 2025 and 2050 through wider access to appropriate antibiotics and better treatment of infections, the report estimates.

“This is an important contribution to understanding how we got to where we are and to provide a rational expectation of the future burden of [resistance] to inform the next steps that can be taken,” says Joseph Lewnard, an epidemiologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

“I think the exposure numbers are probably much higher than what has been reported here,” particularly in countries where there are data gaps, says Timothy Walsh, a microbiologist at the University of Oxford, UK. The numbers suggest the world is falling short of the United Nations' goal of reducing mortality caused by antimicrobial resistance by 2030.

Growing deaths

Researchers analyzed death data and hospital records from 204 countries between 1990 and 2021, focusing on 22 pathogens, 84 combinations of bacteria and antibiotics to which they are resistant, and 11 diseases, including blood infections and meningitis.

The results show that the number of children under 5 dying from drug-resistant infections has fallen by more than 50% over the past 30 years, while the death rate for people over 70 has increased by 80% (see “Resistance Crisis”).

Deaths due to infectionsStaphylococcus aureus— which infects the skin, blood and internal organs — saw the largest increase, increasing by 90.29%.

Many of the deadliest infections between 1990 and 2021 were caused by a group of bacteria that are particularly drug-resistant, called gram-negative bacteria. This category includesEscherichia coliandAcinetobacter baumannii— a pathogen associated with hospital-acquired infections.

Gram-negative bacteria are resistant to carbapenem antibiotics, a class of antibiotics used to treat serious infections, and they can both exchange antibiotic resistance genes with other species and pass them on to offspring. Deaths associated with carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria increased by 149.51% from 50,900 cases in 1990 to 127,000 cases in 2021.

The report estimates that by 2050, antimicrobial resistance could cause 1.91 million deaths each year and a total of 8.22 million people will die from resistance-related diseases. More than 65% of deaths attributed to AMR in 2050 will occur in people over 70 years of age.

“This study shows that we have a problem in the quality of the healthcare system and infection prevention,” says co-author Mohsen Naghavi, a doctor and epidemiologist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Targeted interventions

Regions with the highest predicted death rates are South Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. The researchers emphasize that strategies to combat drug resistance need to be prioritized in low- and middle-income countries.

“We need more global investment and much more real interactive collaboration with low-income countries to ensure they are well equipped,” says Walsh. Strategies must ensure that hospitals in low-income countries have access to diagnostic tools, antibiotics, clean water and sanitation, he adds.

"Most of these deaths don't actually require any new or specific interventions to be prevented. That's an important message they convey," Lewnard says.

Lawmakers should also address the overuse of antibiotics in agriculture, which accelerates bacterial resistance, and invest in research into innovative antibiotics, Walsh said.

The authors hope the report will "provide information about how to develop new drugs, which new drugs to focus on, and which new vaccines to pay attention to," says co-author Eve Wool, research manager at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, Washington.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto