About 4.4 billion people drink unsafe water - twice as many the previous estimate – according to one today inSciencepublished study 1. This finding, which indicates that more than half of the world's population lacks access to clean and accessible water, sheds light on gaps in basic health data and raises questions about which estimate better reflects reality.

It's "unacceptable" that so many people don't have access, says Esther Greenwood, an aquatic researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Dübendorf and author of theScience-paper. “There is an urgent need for the situation to change.”

Since 2015, the United Nations has been pursuing access to safely managed drinking water, which is recognized as a human right. Previously, the UN only reported on whether global drinking water sources were 'improved', meaning they were likely protected from external contamination by infrastructure such as backyard wells, interconnected pipes and rainwater collection systems. By this measure, it appeared that 90% of the world's population had their drinking water OK. However, there was little information about whether the water itself was clean, and nearly a decade later, statisticians still rely on incomplete data.

“We really lack data on drinking water quality,” says Greenwood. Today, water quality data only exists for about half of the world's population. That makes it difficult to calculate the exact extent of the problem, Greenwood adds.

Crunch numbers

In 2015 the UN created their sustainability goals to improve people's well-being. One of these is to “achieve universal and equitable access to clean and affordable drinking water for all” by 2030. The organization updated its criteria for safely managed drinking water sources: they must be improved, consistently available, accessible where a person lives, and free from contamination.

Using this framework, the Joint Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Monitoring Program (JMP), a research collaboration between the World Health Organization (WHO) and the UN children's agency UNICEF, estimated that there were 2.2 billion people without access to safe drinking water in 2020. To arrive at this value, the program aggregated data from national censuses, reports from regulators and service providers, and household surveys.

But it assessed drinking water availability differently than Greenwood and her colleagues' method. The JMP checked at least three of the four criteria in a given location and then used the lowest value to represent the overall quality of drinking water in that area. For example, if a city had no data on whether its water source was consistently available, but 40% of the population had no contaminated water, 50% had improved water sources, and 20% had home water access, then the JMP estimated that 20% of that city's population had access to safely managed drinking water. The program then scaled that number across a country's population using a simple mathematical extrapolation.

In contrast, the usedScience-Paper survey responses across the four criteria from 64,723 households in 27 low- and middle-income countries between 2016 and 2020. If a household did not meet any of the four criteria, it was classified as having unsafe drinking water. The team then trained a machine learning algorithm and integrated global geospatial data - including factors such as regional average temperature, hydrology, topography and population density - to estimate that 4.4 billion people lack access to clean drinking water, half of whom access sources contaminated with the pathogenic bacteriumEscherichia coliare contaminated.

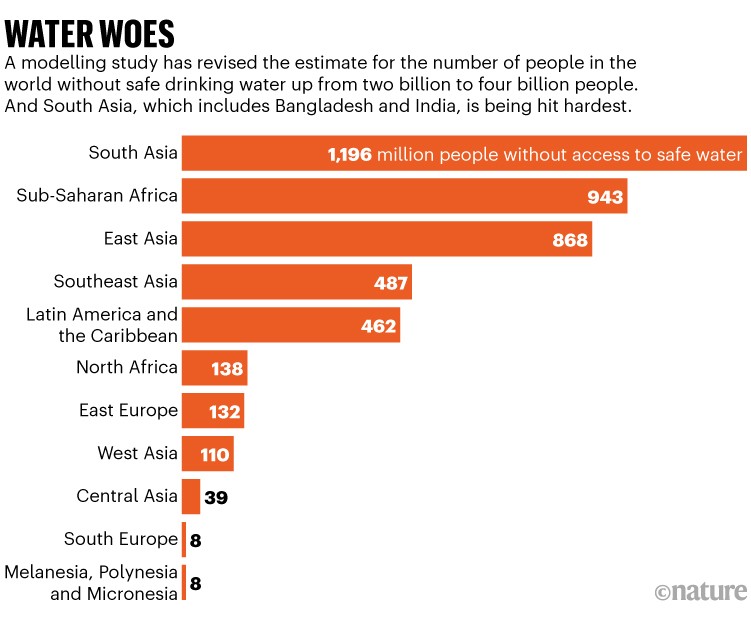

The model also suggested that almost half of the 4.4 billion people live in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (see 'Water problems').

‘A long way to go’

It's "difficult" to say which estimate - the JMP's or the new figure - is more accurate, says Robert Bain, a statistician at UNICEF's Middle East and North Africa regional office based in Amman, Jordan, who contributed to both figures. The JMP combines many data sources but has limitations in its aggregation approach, while the new estimate uses a small data set and scales it up with a sophisticated model, he says.

The study by Greenwood and colleagues really “highlights the need to take a closer look at water quality,” says Chengcheng Zhai, a data scientist at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. Although the machine learning technique used by the team is "very innovative and intelligent," she says, access to water is dynamic, so the estimate may still not be entirely accurate. Wells can be free for a dayE.coliand become contaminated the next day, and household surveys don't capture this, Zhai suggests.

“No matter what number you use – two billion or four billion – the world has a long way to go” to ensure that people’s basic rights are met, Bain says.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto