AI-generated images endanger science – this is how researchers want to recognize them

Researchers are fighting against AI-generated fake images in scientific publications. New methods of detection are developing.

AI-generated images endanger science – this is how researchers want to recognize them

Scientists manipulating numbers and mass producing fake papers Mandatory publishers – problematic manuscripts have long been a nuisance in scientific literature. Scientific detectives work tirelessly, to expose this wrongdoing and correct the scientific record. But their job is becoming increasingly difficult as a new, powerful tool for fraudsters has emerged: generative artificial intelligence (AI).

“Generative AI is developing very quickly,” says Jana Christopher, Image Integrity Analyst at FEBS Press in Heidelberg, Germany. “People who work in my area – image integrity and publishing policies – are becoming increasingly concerned about the possibilities it presents.”

The ease with which generative AI tools texts, images and data raises fears of an increasingly unreliable scientific literature, flooded with fake numbers, manuscripts and conclusions that are difficult for humans to detect. An arms race is already emerging as integrity specialists, publishers and technology companies work diligently to Develop AI tools, which can help quickly identify deceptive, AI-generated elements in specialist articles.

“It’s a frightening development,” says Christopher. “But there are also smart people and good structural changes being proposed.”

Research integrity experts report that although AI-generated text is already permitted under certain circumstances by many journals, using such tools to create images or other data may be considered less acceptable. “In the near future, we may be okay with AI-generated text,” says Elisabeth Bik, image forensics specialist and consultant in San Francisco, California. “But I draw the line when it comes to generating data.”

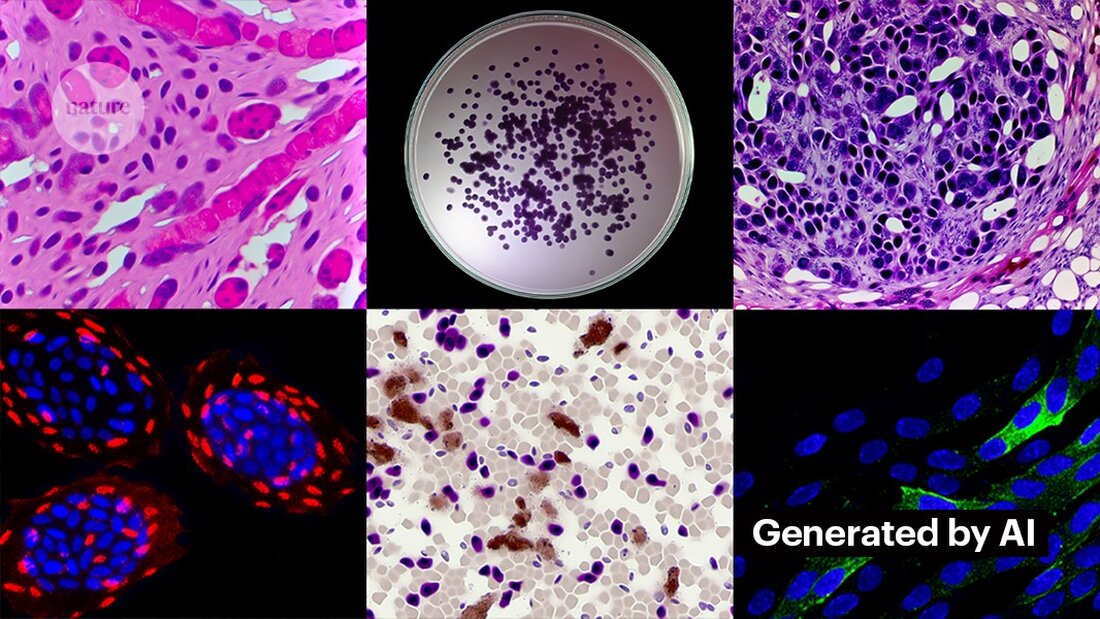

Bik, Christopher, and others suggest that data, including images, created with generative AI are already widely used in literature, and that mandatory publishers are using AI tools to produce manuscripts in volume (see ‘Quiz: Can You Spot AI Forgeries?’).

Identifying AI-produced images poses an enormous challenge: they are often almost impossible to distinguish from real images with the naked eye. “We feel like we come across AI-generated images every day,” says Christopher. “But unless you can prove it, there’s really very little you can do.”

There are some clear examples of the use of generative AI in scientific images, like the now infamous image of a rat with absurdly large genitals and nonsensical labels, created with the Midjourney image tool. The graphic, published by a trade magazine in February, caused a storm on social media and was withdrawn a few days later.

However, most cases are not so obvious. Figures created using Adobe Photoshop or similar tools before the advent of generative AI - particularly in molecular and cellular biology - often contain striking features that can be recognized by detectives, such as identical backgrounds or the unusual lack of streaks or spots. AI-generated characters often do not show such characteristics. “I see a lot of papers that make me think that these Western blots don't look real - but there's no smoking gun,” says Bik. "All you can say is that they just look strange, and of course that's not enough evidence to contact the editor."

However, there are signs that AI-generated characters are appearing in published manuscripts. Texts written using tools like ChatGPT are increasing in articles, evident by typical chatbot phrases that authors forget to remove and distinctive words that AI models tend to use. “So we have to assume that this also happens for data and images,” says Bik.

Another indication that fraudsters are using sophisticated imaging tools is that most of the problems investigators are currently finding appear in works that are several years old. “In recent years we have seen fewer and fewer problems with images,” says Bik. “I think most people who were caught manipulating images started creating cleaner images.”

Creating clean images with generative AI is not difficult. Kevin Patrick, a scientific image detective known as Cheshire on social media, has demonstrated how easy it can be and published his findings on X. Using Photoshop's AI tool Generative Fill, Patrick created realistic images - which could appear in scientific papers - of tumors, cell cultures, Western blots and more. Most images took less than a minute to create (see ‘Generating False Science’).

“If I can do that, then surely those who are paid to create fake data will do it too,” Patrick says. “There is probably a whole lot of other data that could be generated using tools like this.”

Some publishers report finding evidence of AI-generated content in published studies. This includes PLoS, which has been alerted to suspicious content and found evidence of AI-generated text and data in articles and submissions through internal investigations, says Renée Hoch, editor of PLoS's publication ethics team in San Francisco, California. (Hoch notes that the use of AI is not prohibited in PLoS journals and that the AI policy is based on author responsibility and transparent disclosures.)

Other tools could also provide opportunities for people who want to create fake content. Last month researchers published a 1 generative AI model to create high-resolution microscope images – and some integrity specialists expressed concerns about this work. “This technology can easily be used by people with bad intentions to quickly create hundreds or thousands of fake images,” says Bik.

Yoav Shechtman of the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, the tool's creator, says the tool is useful for creating training data for models because high-resolution microscope images are difficult to obtain. But he adds that it is not useful for generating fakes because users have little control over the results. Existing image editing software such as Photoshop is more useful for manipulating figures, he suggests.

Although human eyes may not be able to Recognize AI-generated images, AI could possibly do this (see ‘AI images are difficult to recognize’).

The developers of tools like Imagetwin and Proofig, which use AI to detect integrity problems in scientific images, are expanding their software to filter images created by generative AI. Because such images are so difficult to recognize, both companies are creating their own databases of generative AI images to train their algorithms.

Proofig has already released a feature in its tool for recognizing AI-generated microscope images. Co-founder Dror Kolodkin-Gal in Rehovot, Israel, says that in testing with thousands of AI-generated and real images from articles, the algorithm correctly identified AI images 98% of the time and had a false positive rate of 0.02%. Dror adds that the team is now trying to understand what exactly their algorithm detects.

“I have high hopes for these tools,” says Christopher. However, she notes that their results must always be evaluated by experts who can verify the problems they indicate. Christopher has not yet seen any evidence that AI image recognition software is reliable (Proofig's internal evaluation has not yet been published). These tools are “limited, but certainly very useful in allowing us to scale our submission review efforts,” she adds.

Many publishers and research institutions are already using it Proof and Imagetwin. For example, Science journals use Proofig to check integrity issues in images. According to Meagan Phelan, communications director for Science in Washington DC, the tool has not yet discovered any AI-generated images.

Springer Nature, Nature's publisher, is developing its own text and image detection tools, called Geppetto and SnapShot, which flag irregularities that are then evaluated by humans. (The Nature news team is editorially independent of its publisher.)

Publishing groups are also taking steps to respond to AI-generated images. A spokesman for the International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical (STM) Publishers in Oxford, UK, said it was taking the issue "very seriously" and was responding to initiatives such as United2Act and the STM Integrity Hub, which addresses current issues with compulsory publishing and other academic integrity issues.

Christopher, who leads an STM working group on image alterations and duplications, says there is a growing awareness that it will be necessary to develop ways to verify raw data - for example, by labeling images taken with microscopes with invisible watermarks similar to those used Watermarks in AI-generated texts – that could be the right way. This requires new technologies and new standards for device manufacturers, she adds.

Patrick and others worry that publishers aren't acting quickly enough to address the threat. “We fear that this will be just another generation of problems in the literature that they don't address until it's too late,” he says.

Still, some are optimistic that the AI-generated content appearing in articles today will be discovered in the future.

“I have every confidence that the technology will improve to the point where it recognizes the data that is being created today – because at some point this will be considered relatively coarse,” says Patrick. "Fraudsters shouldn't sleep well at night. They could fool the current process, but I don't think they can fool the process forever."

-

Saguy, A. et al. Small Meth. https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.202400672 (2024).

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto