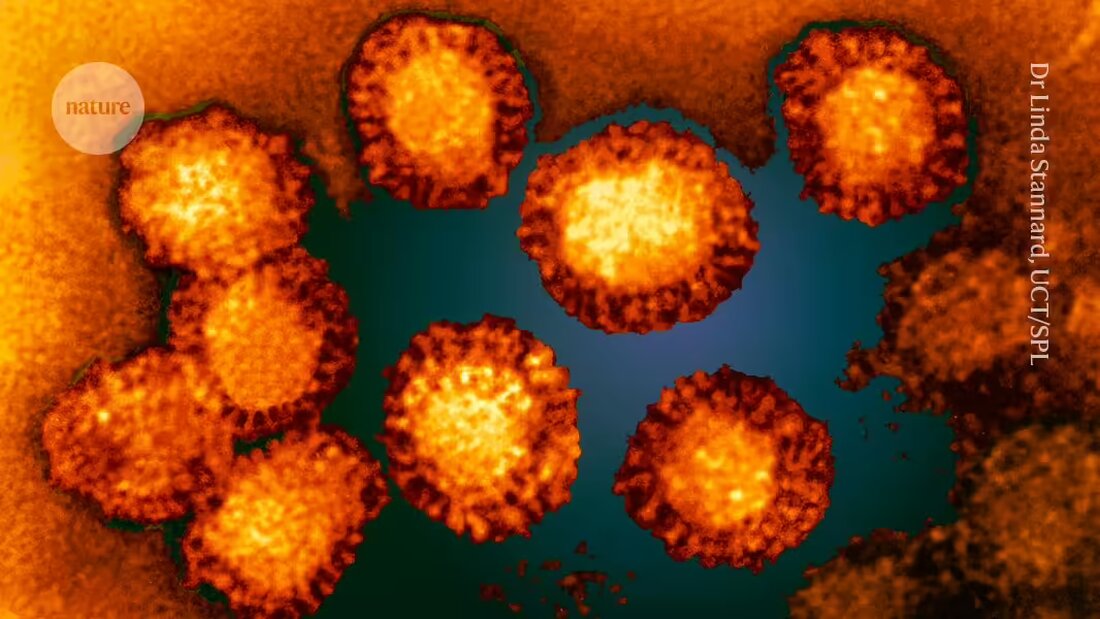

A new database for researchers to share the genomes of dangerous viruses promises to solve many of the problems that hamper existing alternatives. But first researchers have to be convinced to use them.

Pathoplexus - a combination of pathogen and plexus - was launched last month, and the team of scientists behind the database hope it will motivate more researchers to share genetic sequences of known and emerging viruses with public health importance.

Sharing sequences as quickly as possible is important for identifying new viruses and tracking changes that could make them more dangerous to people, as well as for developing vaccines, explains Edward Holmes, a virologist at the University of Sydney, Australia.

Pathoplexus is currently focused on four viruses that are not specifically listed in other databases: Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, Ebola Sudan, Ebola Zaire, and West Nile virus. More pathogens will be added later, the team said.

Existing hurdles

Among the largest existing repositories is GenBank in the United States, which offers unrestricted access to its genomic data. But public access means that, in theory, anyone can use the data to publish scientific articles without acknowledging the data owners. This has discouraged scientists, particularly from low-income countries, from sharing their data quickly, such as during a public health emergency. An alternative repository, GISAID, requires users to register, acknowledge data owners, and do their best to cooperate with the owners. The database was developed to ensure the rights of data submitters.

GISAID has been extremely helpful during the COVID-19 pandemic popular and contains nearly 17 million sequences from SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19. However, researchers have concerns about the transparency in its governance, how it mediates recognition disputes, and how it imposes sanctions on those it believes have violated the Terms of Service.

“GISAID has caused a lot of frustration in recent years,” says Spyros Lytras, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Tokyo. "From these experiences, the scientific community has learned how we can do better. A reset is what we need as a community, and Pathoplexus could be the solution."

A GISAID representative said in an email that the trust it has with the scientific community is strong and that more than 70,000 researchers use the site. The roles of its governance bodies and funders are presented on the website, and their terms of use have not changed since its founding in 2008, the representative said.

Build trust

Pathoplexus offers some protections for users. For example, researchers can set restrictions on how their data can be used, for example it cannot be used as the central focus of scientific publications for up to a year without their express permission. This should give data owners enough time to submit a manuscript about their results.

Users must also acknowledge the data owners in their publications. “We intend to build a community where researchers have confidence that their contributions are respected and properly recognized,” says Jamie Southgate, a member of Pathoplexus and director of operations for the global coalition Public Health Alliance for Genomic Epidemiology based in Cape Town, South Africa.

Pathoplexus will not block anyone who violates the Terms of Use from accessing the Site, which GISAID has done so in rare cases. Instead, the team will contact journals to ensure that the published data is used in accordance with the way in which it was shared, explains Emma Hodcroft, co-founder of Pathoplexus and a molecular epidemiologist at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel, Switzerland. “We tried to make the conditions incredibly clear,” she says.

“It's a good, clever solution,” says Senjuti Saha, a molecular microbiologist at the Child Health Research Foundation in Dhaka, who supports the practice of contacting publishers. “That’s how it should be.” She thinks that Pathoplexus' transparency will increase trust within the scientific community.

But it's still too early to say whether the repository will solve current data sharing problems, says Saha. “It’s an excellent and fantastic first step.”

Users may also tend to share sequences in local databases. In China, for example, researchers are more likely to publish sequences of emerging viruses in Chinese databases, says Shi Mang, an evolutionary biologist at Sun Yat-sen University in Shenzhen, China, who also sits on Pathoplexus' scientific advisory board. But for established viruses, they will likely use repositories with well-maintained collections that Pathoplexus offers.

Improved user experience

The developers of Pathoplexus have tried to improve the user experience, including by making uploading as easy as possible. Pathoplexus also checks the sequence data and accompanying information for errors and helps organize viruses into subtypes. “That’s actually what drew me to this database,” Shi says. Incorrect sequences in current repositories can significantly hinder researchers, he adds.

So far, Pathoplexus has used GenBank data for the four viruses to populate the site. Thousands of visitors have already accessed the site and 50 have created accounts to submit data, but no one has submitted sequences so far, Hodcroft explains. “We didn’t expect large amounts of data for the pathogens we started with.”

Researchers working on other viruses will have to wait until the database expands to include them. In order to expand, the team needs to secure long-term financing. The site is currently run by volunteers and donated computer time, which will end in about six months. Hodcroft says her current goal is to attract donors. “I’m cautiously optimistic.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto