Scientists have for the first time Quantum entanglement observed — a state in which particles fuse together and lose their individuality so that they can no longer be described separately — between quarks. This remarkable event, achieved at CERN, the European particle physics laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland, could pave the way for further studies of quantum information in particles at high energies.

Entanglement has been measured in particles such as electrons and photons for decades, but it is a delicate phenomenon and is easiest to measure in low-energy or "quiet" environments, such as the ultra-cold refrigerators that Quantum computers accommodate. Particle collisions, such as those between protons Large Hadron Collider from CERN, are comparatively loud and high-energy, making it much more difficult to measure entanglement from the debris — akin to listening for a whisper at a rock concert.

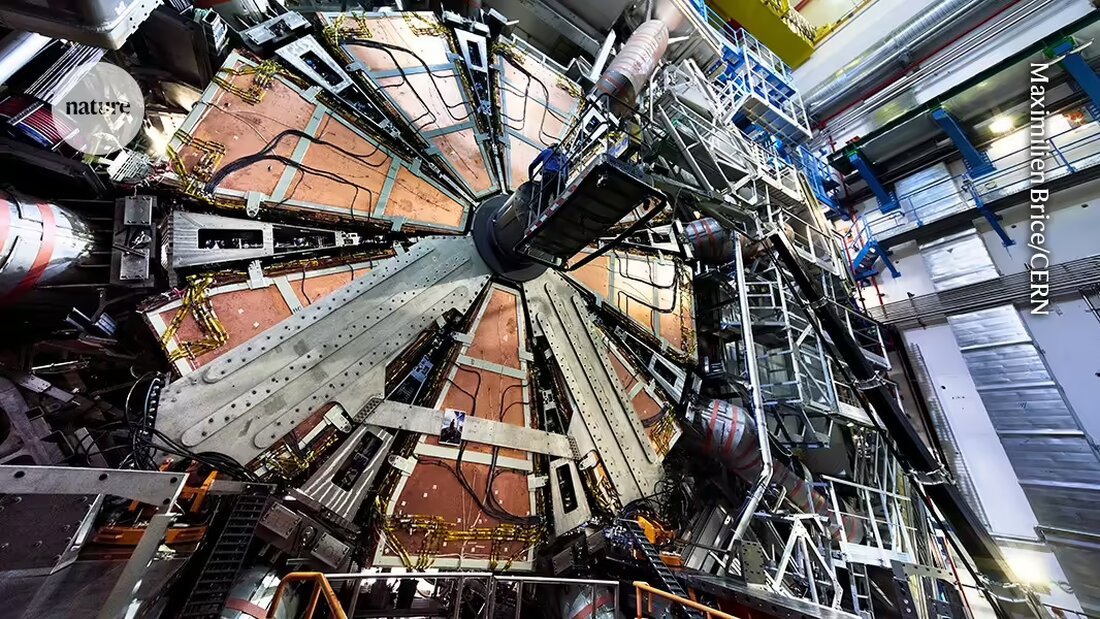

To observe entanglement at the LHC, physicists working on the ATLAS detector analyzed about a million pairs of top and antitop quarks — the heaviest of all known elementary particles and their antimatter counterparts. They found statistically overwhelming evidence of entanglement, which they announced last September and in the Journal todayNature 1describe in detail. Physicists working on the LHC's other main detector, CMS, also confirmed the entanglement observation in a report published in June on the preprint server arXiv 2.

“It's really interesting because it's the first time you can study entanglement at the highest possible energies, which is achieved with the LHC,” says Giulia Negro, a particle physicist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, who was involved in the CMS analysis.

Scientists had no doubt that top quark pairs could be entangled. The Standard model of particle physics — the current best theory about elementary particles and the forces through which they interact — is based on quantum mechanics, which describes entanglement. Still, researchers say the latest measurement has value.

“You really don't expect to be able to break quantum mechanics, do you?” says Juan Aguilar-Saavedra, a theoretical physicist at the Institute of Theoretical Physics in Madrid. “An expected result shouldn’t stop you from measuring important things.”

Transient tops

During a coffee break years ago, Yoav Afik, an experimental physicist now at the University of Chicago in Illinois, and Juan Muñoz de Nova, a solid matter physicist now at the Complutense University of Madrid, wondered whether it was possible to observe entanglement at a collision accelerator. Their conversation turned into a paper 3, which demonstrated a way to measure entanglement using top quarks.

Pairs of top and antitop quarks created after a proton collision live unimaginably short lives — just 10−25seconds. They then break down into longer-lived particles.

Previous studies 4had revealed that top quarks can have correlated “spin” states during their short lifetimes, a quantum property that is angular momentum. Afik and Muñoz de Nova's insight was that this measurement could be extended to show that the spin states of top quarks are not just correlated, but actually entangled. You defined a parameter,Dto describe the level of correlation. IfDis smaller than −⅓, the top quarks are entangled.

Part of what ultimately made Afik and Muñoz de Nova's proposal successful is the short lifetime of the top quarks. “You could never do this with lighter quarks,” says James Howarth, an experimental physicist at the University of Glasgow, UK, who was part of the ATLAS analysis along with Afik and Muñoz de Nova. Quarks don't like to separate, so they split after just 10−24Seconds begin to mix to form hadrons such as protons and neutrons. But a top quark decays quickly enough that it doesn't have time to become "hadronized" and lose its spin information through mixing, Howarth explains. Instead, “all this information is transferred to its decay products,” he adds. This meant researchers could measure the properties of the decay products to work backwards and derive the properties, including spin, of the parent top quarks.

After making an experimental measurement of the spins of the top quarks, the teams compared their results with theoretical predictions. But the models of top quark production and decays did not agree with the detector's measurements.

Researchers at ATLAS and CMS struggled with the uncertainties in different ways. For example, the CMS team found that adding “toponium” — a hypothetical state in which a top and antitop quark are bonded together — to their analyzes helped better align theory and experiment.

In the end, both experiments easily reached the −⅓ entanglement limit, with ATLASDwith −0.537 and CMS with −0.480.

Crown placement

Success in observing entanglement in top quarks could improve researchers' understanding of the physics of top quarks and pave the way for future high-energy tests of entanglement. Other particles, like the Higgs boson, could even be used to perform a Bell test, an even more rigorous study of entanglement.

The top quark experiment could change the way physicists think, says Afik. “It was a little difficult at first to convince the community” that the study was worth the time, he says. After all, entanglement is a cornerstone of quantum mechanics and has been verified time and again.

But the fact that entanglement has not been thoroughly explored in high-energy regions is reason enough for Afik and the other followers of the phenomenon. “People have realized that you can now start using hadron collision accelerators and other types of accelerators for these tests,” says Howarth.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto