Stem cells cure diabetes in women – world premiere

A 25-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes produced insulin on her own after a stem cell transplant - a groundbreaking success.

Stem cells cure diabetes in women – world premiere

A 25-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes began producing her own insulin less than three months after a transplant of reprogrammed stem cells 1. She is the first person with the condition to be treated with cells taken from her own body.

“I can eat sugar now,” the woman, who lives in Tianjing, said in a phone call to Nature. It's been more than a year since the transplant and she says, "I enjoy eating everything - especially hotpot." The woman asked to remain anonymous to protect her privacy.

James Shapiro, a transplant surgeon and researcher at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, describes the results of the operation as remarkable. “They completely reversed the patient’s diabetes, which previously required significant amounts of insulin.”

The one in the magazine todayCellpublished study follows results from a separate group from Shanghai, China, who reported in April that they successfully transplanted insulin-producing islets into the liver of a 59-year-old man with type 2 diabetes 2. These islets also came from reprogrammed stem cells taken from the man's body, and he has since stopped taking insulin.

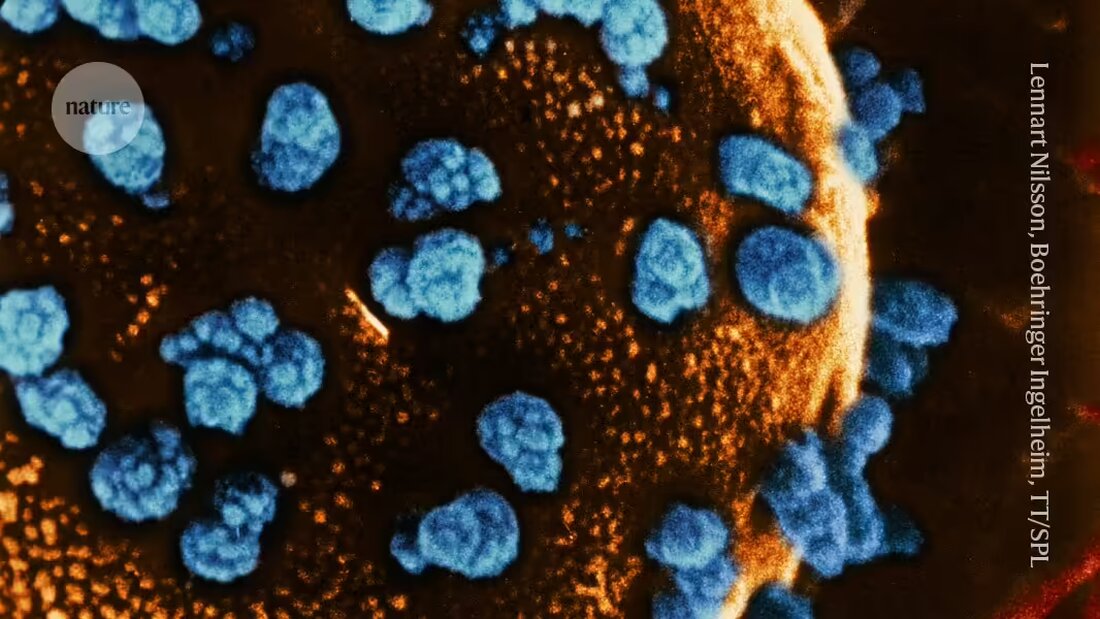

These studies are among a handful of groundbreaking attempts to use stem cells to treat diabetes, which affects nearly half a billion people worldwide. The majority of these patients have type 2 diabetes, in which the body does not produce enough insulin or the body's ability to use the hormone decreases. At Type 1 diabetes On the other hand, the immune system attacks the islet cells in the pancreas.

Islet transplants can treat the disease, but there are not enough donors to meet increasing demand. Recipients must also take immunosuppressive medications to prevent the body from rejecting the donor tissue.

Stem cells can be used to grow any tissue in the body and can be cultured indefinitely in the laboratory. This means they potentially provide an unlimited source of pancreatic tissue. By using tissue derived from a person's own cells, researchers also hope to avoid the need for immunosuppressants.

In the first attempt of its kind, Deng Hongkui, a cell biologist at Peking University in Beijing, and his colleagues extracted cells from three people with type 1 diabetes and reverted them into one pluripotent state, from which they could be formed into any cell type in the body. This reprogramming technology was developed almost two decades ago by Shinya Yamanaka developed at Kyoto University in Japan. Deng and his colleagues modified the technique 3: Instead of introducing proteins that trigger gene expression, as Yamanaka had done, they exposed the cells small molecules. This offered more control over the process.

The researchers then used the chemically induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) to create 3D Clusters of islands to generate. They tested the safety and effectiveness of the cells on mice and non-human primates.

In June 2023, in a procedure lasting less than 30 minutes, they injected the equivalent of about 1.5 million islets into the woman's abdominal muscles - a new site for islet transplants. Most islet transplants are injected into the liver, where the cells cannot be observed. By placing them in the abdomen, researchers could monitor the cells using magnetic resonance imaging and potentially remove them if necessary.

Two months later the woman produced enough insulin, to survive without supplies, and it has maintained this level of production for more than a year. At this point, the woman had stopped experiencing dangerous spikes and drops in blood sugar levels that remained within a target range for over 98% of the day. “This is remarkable,” says Daisuke Yabe, a diabetes researcher at Kyoto University. “If this can be applied to other patients, that will be wonderful.”

The results are intriguing but need to be replicated in more people, says Jay Skyler, an endocrinologist at the University of Miami, Florida, who studies type 1 diabetes. Skyler also wants to see the woman's cells produce insulin for up to five years before he considers her "cured."

Deng reports that the results for the other two participants are "also very positive," and they will reach the one-year mark in November, after which he hopes to expand the study to another 10 or 20 people.

Because the woman was already receiving immunosuppressants from a previous liver transplant, researchers could not evaluate whether the iPS cells reduced the risk of transplant rejection.

Even if the body does not reject the transplant because it does not view the cells as “foreign,” people with type 1 diabetes are still at risk of the body attacking the islets because of their autoimmune disease. Deng explains that they did not observe this in the woman due to the immunosuppressants they were taking, but they are trying to develop cells that can escape this autoimmune reaction.

Transplants using the recipient's own cells have advantages, but the procedures are difficult to scale and commercially implement, researchers say. Several groups have begun clinical trials of islet cells created from donor stem cells.

Preliminary results from a study led by Vertex Pharmaceuticals in Boston, Massachusetts, were published in June. A dozen participants with type 1 diabetes received islets derived from donated embryonic stem cells and injected into the liver. All were treated with immunosuppressants. Three months after transplantation, all participants began insulin to produce when glucose was present in their blood 4. Some had lost their insulin dependence.

Last year, Vertex launched another trial in which islet cells derived from donated stem cells were placed into a device designed to protect them from immune system attacks. It was transplanted into a person with type 1 diabetes who was not receiving immunosuppressants. “This study is ongoing,” says Shapiro, who is involved in the investigation and wants to involve 17 people.

Yabe also plans to start a trial using islet cells made from donor iPS cells. He plans to develop and surgically place layers of islets in the abdominal tissue of three people with type 1 diabetes who are receiving immunosuppressants. The first participant is expected to be transplanted early next year.

-

Wang, S. et al. Cell 187, 1–13 (2024).

-

Wu, J. et al. Cell Discov. 10, 45 (2024).

-

Guan, J. et al. Nature 605, 325–331 (2022).

-

Reichman, T.W. et al. Diabetes 72, 836-P (2023).

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto