A newly designed 'brain alarm clock' can determine whether a person's brain is aging faster than you chronological age would suspect 1. The brain ages faster in women Countries with more inequality and in Latin American countries, the alarm clock shows.

"The way your brain ages isn't just about years. It depends on where you live, what you do, your socioeconomic level, the level of pollution in your environment," says Agustín Ibáñez, the study's lead author and a neuroscientist at Adolfo Ibáñez University in Santiago. “Any country that wants to invest in people’s brain health must address structural inequalities.”

The work is "really impressive," says neuroscientist Vladimir Hachinski of Western University in London, Canada, who was not involved in the study. She was born on August 26th inNature Medicinepublished.

Just connect

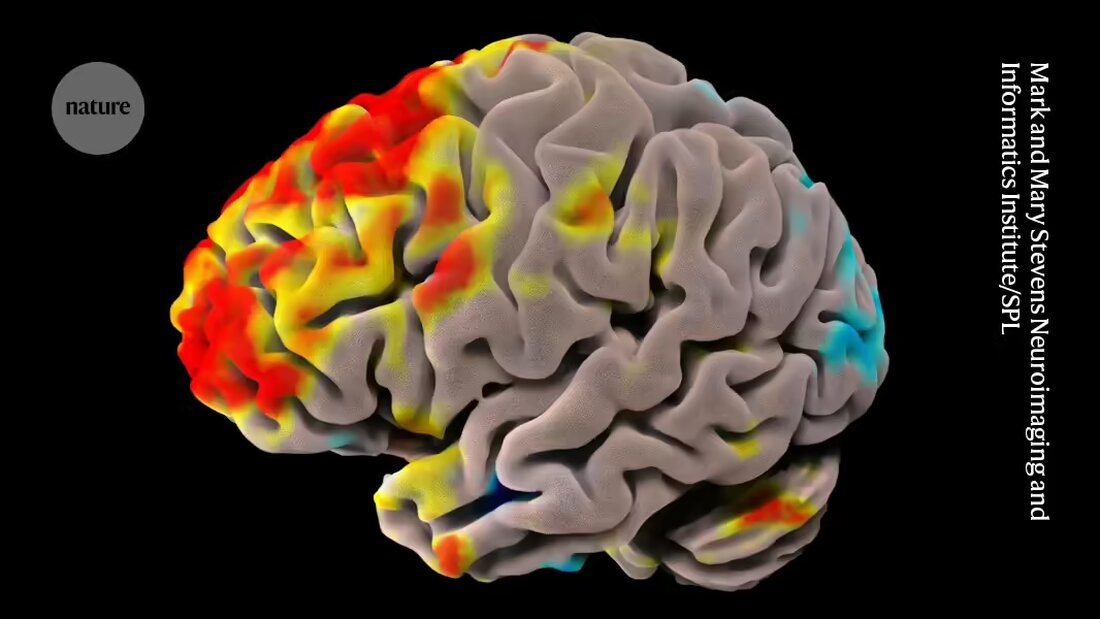

The researchers studied brain aging by studying a complex form of functional connectivity evaluated, a measure of the extent to which different brain regions interact with one another. Functional connectivity generally declines with age.

The authors used data from 15 countries: 7 (Mexico, Cuba, Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Chile and Argentina) in Latin America or the Caribbean and 8 (China, Japan, the United States, Italy, Greece, Turkey, the United Kingdom and Ireland) that are not. Of the 5,306 participants, some were healthy, some had Alzheimer's disease or another form of dementia, and some had mild cognitive impairment, a precursor to dementia.

The researchers measured the participants' resting brain activity - when they were not doing anything in particular functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or electroencephalography (EEG). The first technique measures blood flow in the brain, and the second measures brain wave activity.

The authors calculated the functional connectivity of each person's brain and fed this data into two deep learning models trained on functional connectivity to predict brain age, one for fMRI data and one for EEG data. They were then able to calculate each person's "brain age gap" - the difference between their chronological age and their estimated brain age from functional connectivity. For example, a brain age advantage of ten years would mean that brain connectivity is roughly equivalent to that of someone ten years older than you.

Unequal gaps

The models showed that people with Alzheimer's or another type of dementia had larger brain age gaps than those with mild cognitive impairment and healthy controls.

Participants from Latin America or the Caribbean had, on average, larger brain age gaps than those from other regions. Latin America is one of the most unequal regions in the world, says Ibáñez, and he thinks that's why the brains of people from this region age faster. Structural socio-economic inequality, Exposure to air pollution and Health disparities have been linked to larger brain age gaps, particularly in people from Latin America.

Additionally, women living in countries with high gender inequality - particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean - tended to have larger brain age gaps than men in those countries.

Different clocks, different continents

Quantifying brain aging in such a geographically diverse sample is a phenomenal achievement, says Hachinski. He believes the conclusion that brain age gaps vary is solid, but he cautions that functional connectivity is just one way to measure brain health and that someone could have a lot of brain connectivity while suffering from, for example, conditions like depression suffers from poor mental health or anxiety. Neuroscience is “not good at measuring shapes,” he says.

One possible source of inconsistency in the data is the diversity of fMRI machines and EEGs - spread across 15 nations - that provided the brain scans. For example, poorer countries may have had older equipment that produced lower quality data than those from wealthier countries. However, Ibáñez found no association between low data quality and larger brain age gaps or higher structural inequality.

Currently, Ibáñez's team is studying whether brain age gaps are related to national income by comparing brain age gaps in groups from Asian countries and the United States and using data from Adds 'epigenetic' clocks that determine biological age by studying chemical changes measure on DNA. Ultimately, Ibáñez hopes the data will help develop personalized medical approaches based on the full biological diversity of people's brains around the world.

“We need to understand this diversity,” says Ibañez. “We cannot create a truly global science on dementia without addressing this.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto