World first: Therapy with donor cells leads to remission of autoimmune diseases

A novel therapy using donor-derived, CRISPR-modified immune cells shrinks autoimmune diseases in three patients in China.

World first: Therapy with donor cells leads to remission of autoimmune diseases

A woman and two men with severe autoimmune diseases have experienced remission after treatment with bioengineered and CRISPR-modified immune cells 1. These three people from China are the first people with autoimmune diseases to be treated with immune cells made from donor cells, rather than having these cells taken from their own bodies. This advance is the first step toward mass production of such therapies.

One recipient, Mr. Gong, a 57-year-old man from Shanghai with systemic sclerosis, which affects connective tissue and can cause skin stiffening and organ damage, reported that three days after therapy he noticed his skin loosening and that he was able to begin moving his fingers and opening his mouth again. He returned to work two weeks later. “I feel very good,” he says more than a year after the treatment.

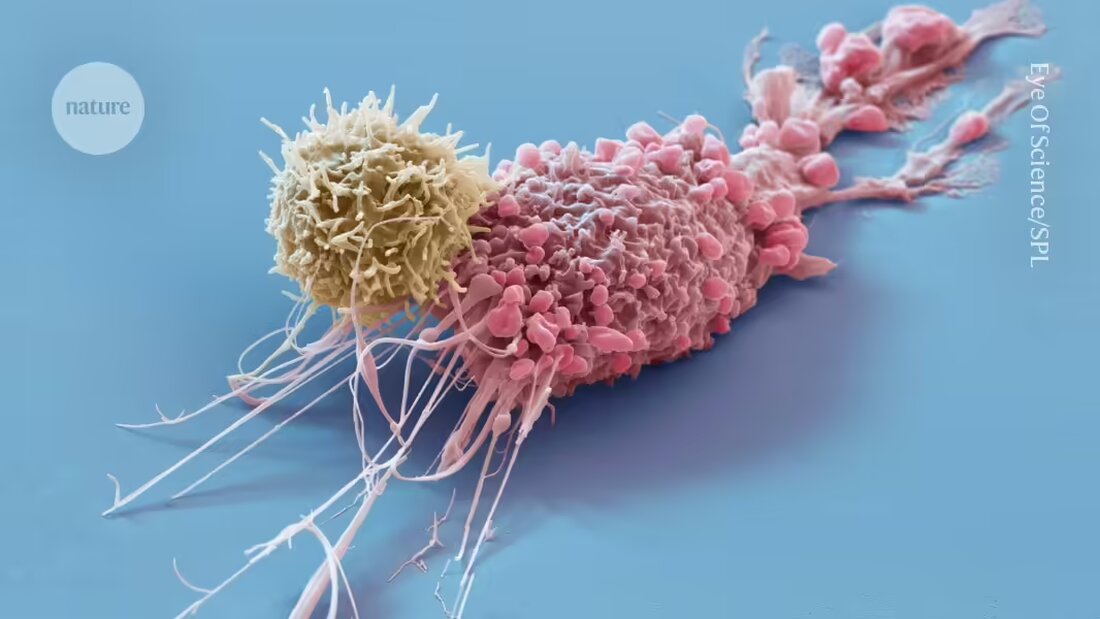

Engineered immune cells, known as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, have been used in the treatment of blood cancers great hope shown — a handful of products are in the United States approved — and there is potential in the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as Lupus and Multiple sclerosis, in which aberrant immune cells produce autoantibodies that attack the body's own tissues. However, the therapy usually relies on a person's own immune cells, making it expensive and time-consuming.

Therefore, researchers have begun developing CAR T therapies from donated immune cells. If successful, pharmaceutical companies could scale production, likely increasing the Cost and production times can be significantly reduced. Instead of making one treatment for one person, therapies for more than a hundred people could be made from one donor's cells, said Lin Xin, an immunologist at Tsinghua University in Beijing. CAR T cells from donor cells have already been used to treat cancer patients, but so far with limited success 2.

Autoimmune diseases

The study, led by Xu Huji, a rheumatologist at Naval Medical University in Shanghai, is the first to report results for autoimmune diseases. These were published last month in the journal Cell. Recipients remained in remission more than six months after treatment. According to Xu, another two dozen people have now received the donor cell treatment and a slightly modified product. The results were mostly positive, he says.

“The clinical results are phenomenal,” said Lin, who is leading a separate study using donor-derived CAR T cells to treat lupus.

The therapy's success and safety look promising, but it needs to be demonstrated in many more people before researchers can draw conclusions about its widespread use, says Christina Bergmann, a rheumatologist at Erlangen University Hospital in Germany.

But if it is successful in more people over a longer period of time, it could be "paradigm-shifting," said Daniel Baker, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Over 80 autoimmune diseases are linked to faulty immune cells.

Healthy donor

CAR T-cell therapy typically involves collecting immune cells, known as T cells, from the person being treated. These cells are enriched with CAR proteins that attack B cells and then infused back into the person's body.

The process for producing CAR T cells from donated immune cells is similar. Xu and his colleagues took T cells from a 21-year-old woman and tagged them with CARs that recognize CD19, a receptor found on the surface of B cells. They used the CRISPR–Cas9 genetic engineering tool to turn off five genes in the T cells, both to prevent the transplanted cells from attacking the host's body and to prevent the host's immune system from attacking the donor cells.

The first person to receive the treatment was a 42-year-old woman in May 2023 with a type of autoimmune myopathy that attacks skeletal muscle tissue, causing weakness and fatigue. Mr. Gong and another 45-year-old man had an aggressive form of sclerosis. Her treatments began in June and August 2023.

Once injected into the hosts, the CAR T cells began to work. They multiplied and targeted all B cells — including pathogenic cells linked to autoimmune diseases. The bioengineered T cells survived in the recipients for weeks before mostly disappearing. Eventually, new healthy B cells returned while no pathogenic cells remained. A similar reaction has been observed in people with Autoimmune diseases observed who received CAR T cells derived from their own cells 3.

“Complete remission”

Two months after treatment, researchers report that the woman achieved complete remission and maintained that status at her six-month follow-up. Baker notes that although the woman showed significant clinical improvement, he would be more cautious about calling this a complete remission because the evaluation time frame was short. The woman's autoantibodies had fallen to undetectable levels, and her muscle strength and mobility had improved dramatically.

The two men also saw significant improvements in their symptoms — including the regression of scar tissue — as well as a decrease in autoantibody levels.

None of the people experienced an extreme inflammatory reaction known as cytokine release syndrome, which has been seen in some cancer patients receiving CAR-T therapy, and showed no evidence that the transplant had attacked the host. However, researchers are still trying to figure out whether the host rejects the transplant over time.

A key safety concern identified in some people receiving CAR T-cell therapies to treat cancer is this Appearance of new tumors, although researchers are continuing to study whether they are related to therapy. Baker emphasizes that it is too early to know whether people with autoimmune diseases treated with donor-derived CAR T cells are at this risk. “Only time will tell.”

The key question now, says Baker, is whether the same approach will work for more people and how long-lasting the effects will be. “Will these patients remain symptom-free for years?”

-

Wang, X. et al. Cell 187, 4890–4904 (2024).

-

Chiesa, R. et al. N Engl J Med 389, 899–910 (2023).

-

Müller, F. et al. N Engl J Med 390, 687–700 (2024).

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto