While this is happening H5N1 bird flu virus spreads relentlessly in animals around the world, have researchers who want to understand how one human H5N1 pandemic could unfold, a rich source of clues is used: data on the immune system's immune response Influenza.

This information provides clues about who might be most at risk in an H5N1 pandemic. Previous research also suggests that our immune systems would not start from scratch in the event of an encounter with the virus - thanks to previous infections and Vaccinations against other forms of flu. However, this immunity would likely not prevent H5N1 from causing severe harm to global health if a pandemic were to break out.

From feathers to fur

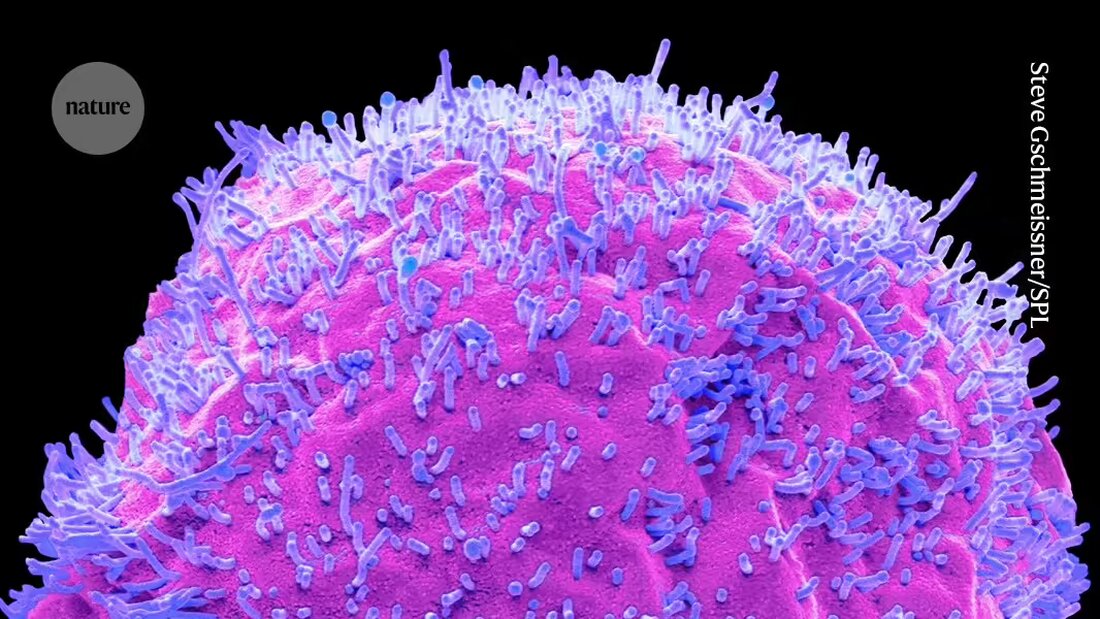

The now rampant H5N1 strain began as an avian pathogen and then spread to mammals. Classified as 'highly pathogenic' due to its lethal effects on birds, it has killed millions of farmed and wild birds worldwide since its first appearance in 1996. 1 It has also spread to a growing list of mammal species, including seals and Foxes, and has claimed more than 460 lives since 2003.

So far, the virus has not yet gained the ability to spread effectively from person to person, which has so far kept the potential for a pandemic at bay. But its repeated jumps from birds to mammals and evidence of transmission among mammals, such as elephant seals (Mirounga leonina) 2, have alarmed researchers who warn that the virus is getting increasing opportunities to spread easily between people.

These concerns were heightened when H5N1 was first detected in US cattle in March – Animals that frequently interact with humans. As of July 8, U.S. health officials have confirmed bird flu infections in nearly 140 dairy herds in 12 states and at 4 dairy farmers.

All workers had mild symptoms, but scientists warn the virus still poses a threat. It's possible that the workers escaped serious illness because they may have caught the H5N1 through contact with milk from infected cows rather than through the usual airborne particles, says Seema Lakdawala, a flu virologist at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia. Or perhaps because the workers may have been infected through the eye rather than the typical route of the mouth or nose.

Malik Peiris, a virologist at the University of Hong Kong, says he is not surprised by these infections "nor is reassured that the mildness of these cases means this virus is mild in nature."

Immune preparation

The inherent virulence of the virus is not the only factor that would shape a pandemic, says Peiris. Another is the state of readiness of the immune system.

Through a combination of previous infection and immunization, people generally have already had significant exposure to the flu by adulthood. Some estimates 3suggest that up to half of the younger population is infected with 'seasonal' flu each year, causing regular waves of infection.

However, exposure to seasonal flu provides limited protection against the new flu strains that could cause pandemics. These strains are genetically different from the circulating seasonal strains, meaning they have less built-up immunity in people and therefore may be more dangerous.

At this time, H5N1 does not spread easily from person to person. But scientists fear that if it gains this ability, it could cause a pandemic because it is genetically different from the seasonal flu viruses currently circulating. Tests of people in the United States have found that few have antibodies to today's H5N1 strain. This suggests that "most of the population would be susceptible to infection with this virus if it were to easily infect people," according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which conducted the tests.

Good news, bad news

But that doesn't mean people are completely unprotected, as exposure to an older pandemic flu strain can protect against a new one, says Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. For example, there were 2009 pandemic caused by the H1N1 swine flu virus 80% of deaths occur in people under 65 4. Older generations were spared due to immunity derived from exposure to different H1N1 strains when they were younger.

Exposure to H1N1 during the 2009 pandemic and at other times may, in turn, provide some protection against the emerging H5N1 strain today. Both the H5N1 and H1N1 viruses have a surface protein called N1, and an immune system that responds to H1N1 could also respond to H5N1. Peiris and his colleagues found that near-universal exposure to H1N1 in 2009 and subsequent years produces antibodies that react to H5N1 in nearly 97% of the samples they collected 5. He is now conducting animal experiments to determine whether this antibody response provides protection against infections and serious illness.

The all-important first case of flu

There is another complicating factor for the immune response to H5N1: A person's first case of the flu could have an outsized impact on their future immunity. In a study published in 2016 6Worobey and his colleagues analyzed nearly two decades of severe infections caused by two subtypes of bird flu, H5N1 and H7N9. They found that people are generally unharmed by the flu strain that most closely matches the one that caused their first flu illness - while they are more susceptible to mismatched strains.

For example, people born before 1968 have likely avoided the effects of H5N1 so far because they likely had their first flu illness at a time when the dominant flu virus in circulation was H5N1. However, those born after 1968 have so far escaped the worst effects of H7N9 because their first exposure to the flu was likely with a virus that matches H7N9 rather than H5N1. Immunity from the first infection provided 75% protection against severe disease and 80% protection against death with a matched bird flu virus, the authors found.

If an H5N1 outbreak were to occur, this first-case effect predicts that older people could be largely spared and younger people would be more vulnerable, Worobey said. “We should have it somewhere between the front and back of the head,” he says.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto